In January, I get an unusual invitation to speak. A local elementary school wants me to be their Black History Month speaker.

I instantly accept. I picture myself engaging a room full of five through eleven-year-olds sitting criss-cross-applesauce on the linoleum floor. What a nice change from what I normally do. Easy. Fun.

But things take a turn. First, I’m told that instead of the entire student body gathering in the multipurpose room, the kids will be in their homerooms and I’ll be beamed to the front of each classroom on a Zoom screen. How am I going to grasp and hold the attention of young kids by Zoom, I wonder. My heart flutters a bit. No one wants to be a failure.

Things go from bad to worse when I’m told that I should begin by reading a book to the kids before telling tidbits from my life’s journey. What a dumb idea, I think. I mean what book can possibly hold the attention of kindergarteners without boring the fifth graders, or vice versa? Plus the internet. Just one lag and I’ll lose them.

I push back hard on this read-a-book suggestion. If I’m being honest, I probably even pouted a little.

But, I’d already said yes to the gig so I can’t renege.

I resign myself to being a failure.

_____

It’s morning of. I’m in my kitchen. I open my laptop and log onto the Zoom. Four student government leaders, all fifth graders, take turns introducing me.

I open cheerfully, and with gratitude. I’ve decided on a Mister Rogers-esque opening, where I’ll let the audience follow me as I walk to my ultimate destination, which is my desk, located in a shed in my backyard.

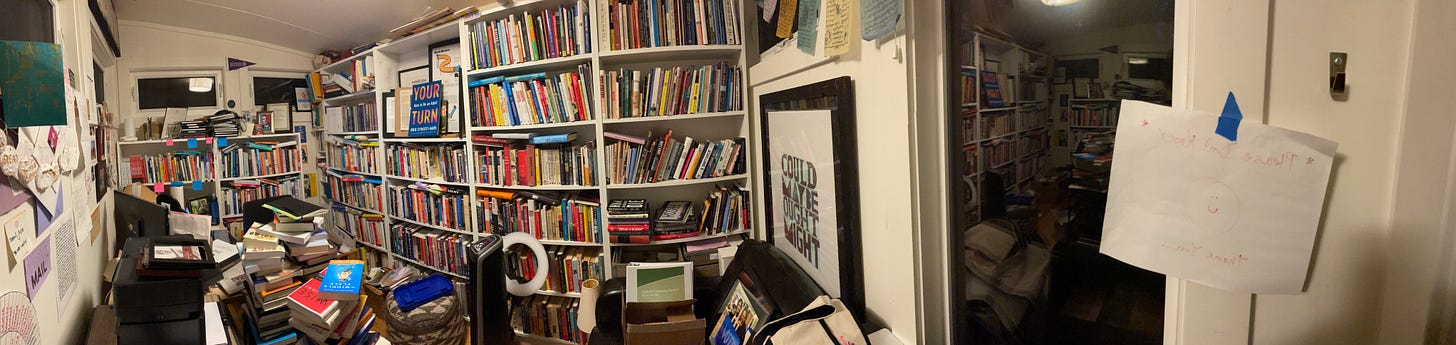

As I walk outside while smiling at the Zoom, I enthusiastically announce that I’m a local author and mom and we’re about to go into my office (pan to the shed) which is full of … Can you guess (I tease) … and then I walk inside and do a panorama on the thousand or so books that are in here.

I sit down at my desk all the while smiling and continuing to chat animatedly with a crowd I cannot see. I’m hoping the kids are listening, but who knows. I set my laptop on the wooden crate that doubles as a computer stand atop my desk and take a deep breath. It’s time for me to read the book.

I’ve chosen I am Ruby Bridges, the story of a six-year-old Black girl who lived in Louisiana in 1960 where she desegregated the all white elementary school in her town. I chose this story first because the librarian swore that yes it would appeal to the spectrum of kids spanning five to eleven years old. Second, because it’s about a kid of an age they can all relate to. Third, it’ll allow me to segue to my own story of being a Black child who was once their age and who dealt with some stuff and persevered and grew up. Fourth because this is a a twentieth-century-story with a protagonist who is still alive; it teaches living history.

The principal takes over and shares her screen, where she advances the Powerpoint slides of the pages of I am Ruby Bridges. My job is to follow along and read aloud. To summon the requisite energy needed to create and sustain attention, I imagine myself before a village of small children, and try to read the book in a way that will reach the soul of each one. I read not only the words but draw attention to what the illustrations are doing to move the story along. All the while I’m doing this I hope to god I’m not lagging, and that small children are not muttering to themselves jezus what the hell is this old lady trying to do here.

I finish the book, check the time, and see that there are still about seven minutes left for me to tell my story. So I begin. I tell of being the child of a Black Daddy and a White Mom. About how when I was three I could tell that some strangers hated Daddy and I began to wonder if they also hated me. How when I was seven I was swimming in a friend’s pool with a bunch of other kids, all white except me, and how one of the kids’ parents pulled their kid out of the pool because she did not want her child swimming with a little Black kid me because Black kids had cooties or something. Watching the clock, I add that when I was ten, I took a test like the one Ruby Bridges took, to see if I could have an advanced learning opportunity at my school, and how despite getting a great score on the test, like Ruby Bridges did, my teacher still did not think I deserved the opportunity.

Time is up. I smile, and say that those experiences made me care about anyone who was mistreated, and made me want to be a part of student government to make things better for everyone, which I did in sixth grade, and in high school, and in college, and again in law school, and I’d even run for and landed a spot in our city government this fall right here in Palo Alto, to try to look out for everybody.

I thank them for listening and wish them well and wait for the principal to end the event.

The principal jumps in and says, “While some of our classrooms have to leave now, if you have a few more minutes, most are available for ten more minutes and maybe some of the children have questions.”

“Absolutely,” I say. Then I hold my breath.

A small child comes to the front of her classroom. “Do you write children’s books?” I tell her no. She tells me I should because she can tell I really care. I thank her.

I grab a piece of paper so I can scribble down the name of the next child so as to be sure to thank her by name when I answer.

A child in another classroom comes forward. “Why were Black kids prevented from going to school with White kids?” I explain that in much of the United States it was once the case that people felt Black kids were inferior or problematic and should not be allowed to attend the same schools as White children. I mention that there weren’t nearly as many Asian and Latino folk in the US at the time so the real difference in those days was between Whites and Blacks.

The voices that come my way are so high and tiny and innocent. The questions as large as these children are small.

The next child asks, “Why are we only reading about Ruby Bridges if this was happening in many schools?” I seize the opportunity to discuss how history and literature are deliberate telling of someone’s stories, and that we must always be curious about whose story is not being told and why. I tell them that my older Black siblings were the first to desegregate a white school in Oklahoma, and as I tell it, and imagine my own kin young and scared and proud, my eyes well up. I tell them that maybe they can hear the tears in my voice because it makes me sad to think about it.

The ten minutes is up. I imagine a bell ringing. But the principal keeps calling on kids.

“What was the worst thing you experienced growing up?” Someone wrote a bad word called the N-word on my locker on my seventeenth birthday, I tell them.

“Why were there no children in the school once Ruby Bridges got there?” Because white parents refused to allow their kids to attend a school if a Black student was there.

“What do I do if people are mean to me because they think I’m different…” I tell her it is important to love herself anyway, and that it’ll get better, and to find a teacher she trusts to talk about this further.

_____

The surprise Q&A portion of the event goes not ten minutes, but twenty-five. Ten-year-olds and eight-year-olds and five-year-olds keep coming to the mic and speak to me through masks and across the ethernet of Zoom. It is the realest clearest conversation about tough stuff I’ve had in a long time. I find myself thinking They’re old enough to know right from wrong but young enough to still speak their mind. I find myself thinking, these are the tough conversations they’re afraid of in so many school districts across America right now.

I finish by telling the children that Ruby Bridges is still alive. That she’s probably a little older than their grandparents. That all of this segregated schools stuff wasn’t that long ago. That we have to tell the stories so we learn from our mistakes and don’t repeat them.

Check out this book. And maybe figure out how you can read an important book to small children. Just be ready to answer their big questions as honestly as you can. They are brave and wise and may just be a breath of fresh air. Maybe even they’ll remind you of who you are.

🏡 You've been in Julie's Pod, an online community of over 12,000 people who want to open up about our lives, be vulnerable, learn and grow, and in so doing help others learn and grow. You can subscribe at the button below.

📚 Here’s what the inside looks like:

🪴The Julie's Pod community grows fastest when you share this post with a friend. So think about who might want to read this piece, and please forward it to them. If you want to just provide the link:

✍ If you left a comment on any post before today, I've probably responded. The comments are always thoughtful so please feel welcome to join the conversation.

☎ For those who can't comment publicly–hey, I realize not everyone is quite the open book I am–I've set up a free confidential hotline 1-877-HI-JULIE where you can leave an anonymous voicemail to let me know what's on your mind, whether about something I’ve written or just something you want to get off your chest and know that someone cares and is listening.

🧐 If you're interested in my work more broadly, check out my website and everywhere that social media happens I'm @jlythcotthaims.

🌲If you’re interested in my work as a city councilmember in Palo Alto, California (the heart of Silicon Valley) check out that website.

© 2023 Love Over Time LLC All Rights Reserved

I love this post and you are exactly right- young people need these conversations! I recently read "I Am Every Good Thing" by Derrick Barnes and Gordon James to a group of 3rd graders. I asked them to respond to the book in a council format. One girl shared a story about how she was the only black girl in her class and how that made her feel. Her parents told her to remember she was a beautiful black girl and to be proud. After each child shared, I asked student to engage in a witness round, where they say something they heard someone else say. Four other third graders said "Beautiful black girl." We ended our time together repeating the last lines of the book: "I am worthy to be loved." What a beautiful morning in Los Angeles.

I was inspired by this. Sadly, that is one of the books under attack by DeSantis in Florida. The children are not the problem. It is the "adults in the room" who hold majorities in too many states. God love the principal of this school. Also, from out of the mouths of babes. Unless they are programmed wrongly, as they were in the South of my youth, they have a wonderful ability to champion fairness, as did my students at the school at which I was teaching when Florida public schools were finally compelled to integrate. Our principal was a champion of acceptance when it came, which made an enormous difference. That was in 1968. How sad we now have such a retrograde governor, state board of education, and legislature. One would have to be a teacher in Florida to truly understand what the governor is doing, and how devastating its effect on Florida educators and students is.